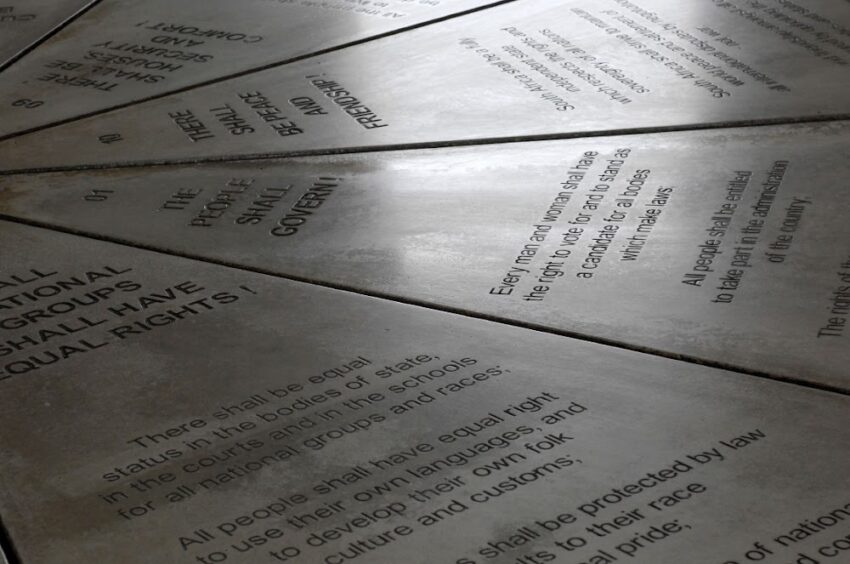

The Freedom Charter, adopted on June 26 1955 in Kliptown, is celebrated as a prophetic blueprint for a future SA – its adoption marking a turning point in a decade when the anti-apartheid struggle had become a mass movement.

It is argued that, within this context of mass mobilisation, the Freedom Charter reflected the mass character and aspirations of the 1950s movement.

Though it was officially adopted in 1955, the idea of convening a Congress of the People was first proposed in 1953 by Prof ZK Matthews, then president of the ANC in the Cape province.

It is estimated that more than 3,000 delegates gathered in Kliptown, representing diverse racial backgrounds in line with the inclusive society envisioned by the Freedom Charter. Kliptown was chosen as a site for the event because no other venue was available to host the historic gathering. Although the apartheid government declared a State of Emergency in Johannesburg to disrupt the assembly, it could not be enforced in Kliptown, a freehold township mainly occupied by Indian families and traders.

Kliptown also held political significance for the ANC. It reinforced its alliance with the Transvaal Indian Congress and the Natal Indian Congress – forged in the 1947 Three Doctors Pact, commonly known as the Afro-Asian political alliance. In addition, the ANC controversially sought to formalise ties with white anti-apartheid organisations, leading to the formation of the Congress Alliance in 1953, the same year Matthews proposed the Congress of the People, which included the Congress of Democrats, a progressive white organisation.

The developments of 1954 laid the groundwork for the Freedom Charter’s adoption the following year. However, the immediate aftermath was marked by severe repression. Police targeted delegates and others involved in anti-apartheid activities, leading to the arrest of 156 activists for treason. The resulting Treason Trial, from 1956 -1959, ended with all charges being withdrawn.

The Sharpeville Massacre of March 1960, and the subsequent state crackdown, silenced all open political activity. From 1960 to 1975, the Freedom Charter faded from public discourse, effectively exiled alongside the banned liberation movements.

In exile, however, it remained a point of ideological contention within the ANC. A group of Africanists – pejoratively labelled the “Gang of Eight” – was expelled in 1975 for opposing the ANC’s increasingly non-racial orientation.

The period between 1975 and 1984 created conditions for the Freedom Charter’s return to political discourse in SA. The ANC established underground structures inside the country to assert its role in the liberation struggle and also reintroduced the Freedom Charter to the masses. But the political fervour that whirling inside SA during the 1970s was shaped by the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) led by Steve Biko – which left little opportunity to galvanise the masses around the Freedom Charter.

The BCM’s emphasis on black identity and psychological liberation overshadowed the multi-racial, class-based vision of the Charter during that period. The turning point came after Black Wednesday on October 19 1977, when the state banned BCM organisations and silenced their media. This repression led to a brief political lull.

But by 1979, student activism was re-emerging, particularly in Soweto. That year, students formed the Congress of South African Students (Cosas), which adopted the Freedom Charter as its founding document – signalling a deliberate shift away from Black Consciousness ideology.

And when unrest broke out in the Vaal on September 3 1984, the Freedom Charter was yet again held up as an inspiration for the youth. The Freedom Charter became the guiding document of all political, cultural and religious formations affiliated to the Mass Democratic Movement (MDM) through the United Democratic Front (UDF). It is this movement, inspired by the MDM, that led the mass mobilisation of 1984 to 1993, rendering the apartheid state ungovernable.

Legal experts and political analysts argue that the 1996 constitution reflects many of the core principles in the Freedom Charter. Yet the document remains contested. Some critics claim it was elitist in its conceptualisation, and that it was the work of a few white intellectuals.